Today, 24 January, The Conversation published a list of 10 books to read on Australia Day. Some of their leading historians chose works that they consider crucial to understanding our culture and history. Notably, for those who are interested in pursuing Truth Telling, five of these books are from the perspectives of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. And another book discusses Australian culture surrounding referendums and how we might return referendums to public ownership, rather than the domination of party politics, negative campaigns and misinformation.

The commentary on these six books has been copied from The Conversation article. Plus, among these expert picks, several other books have been recommended reading for those who are exploring the truths of our First nations people.

Why Warriors Lie Down and Die: Djambatj Mala – Richard Trudgen

Available through SA Libraries

When asked to nominate a book I consider essential to understanding Australian history, a few come to mind. Clarrie Cameron’s Elephants in the Bush and Other

Yamatji Yarns, Busted Out Laughing: Dot Collard’s Story, and Robert Merritt’s The Cake Man show the gentle strength and beauty of Aboriginal thought and language in the face of recent brutality. David Burramurra’s Oceanal Man: An Aboriginal View of Himself – an article rather than a book – shows the depth of history of the continent.

The list of people continuing the storytelling tradition is long. You can’t go wrong reading the stories of Bill Neidjie or Charlie McAdam.

I would nominate Why Warriors Lie Down and Die: Djambatj Mala by Richard Trudgen as essential to understanding how we got to where we are. The book clearly explains why resurgence is still possible. It is an outstanding representation of Aboriginal voices, and an example of the compelling storytelling that is still emerging from the ancient oral traditions of this place.

Lawrence Bamblett, Senior Lecturer, Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Australian National University

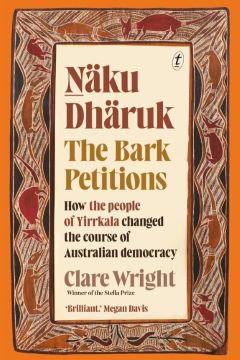

Näku Dhäruk: The Bark Petitions – Clare Wright

Available through SA Libraries

For a book that challenges and deepens your understanding of Australia I would turn to Clare Wright’s new, compelling history of the Yirrkala Bark Petitions, Ṉäku Dhäruk.

This is pacy, epic storytelling about beautiful bilingual documents formally presented by the Yolngu people of north-eastern Arnhem Land to the Commonwealth Parliament in 1963. The dramatic narrative unfolds month by month throughout one year; the book is cinematic in its evocation of land, weather, seasons, politics and people.

How did the Australian government receive this respectful and deeply spiritual petition from a people who have always remained on their land and never ceded it to the invaders?

I think readers know the answer, but as we reflect on our nation’s history, let’s consider paths not taken as well as opportunities that still beckon. Australia is a continental constellation of sovereign peoples whose histories deepen and enrich any understanding of the modern nation. This book takes you on a roller-coaster ride into another world, an Australia most of us hardly know.

Tom Griffiths, Emeritus Professor of History, Australian National University

Truth: the third pillar, alongside Voice and Treaty, of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. We historians have been truth telling about colonisation for decades, and there’s no shortage of books that illuminate why 26 January is better known as Invasion Day.

For this year’s dose of truth, I’d recommend a new release: Clare Wright’s Näku Dhäruk: The Bark Petitions, the third book in her Democracy Trilogy. In this rollicking read, Wright tells how the people of Yirrkala asserted their sovereignty against mining interests and birthed the modern land-rights movement. It’s a tale of resistance and survival in the face of dispossession, but also an extraordinary glimpse into the sophistication of Yolŋu culture and governance. We settlers should be so lucky to live alongside such wisdom.

Yet the true history of this continent is not only contained in history books. Truth telling is sometimes more potent in the creative arts, and I have found First Nations poetry especially affecting. Two personal favourites are Natalie Harkin’s Archival-Poetics and Ambelin Kwaymullina’s Living on Stolen Land. Both remind us that the past isn’t past and – as Kwaymullina puts it – “there is no space of innocence”. Having reckoned with that fact, what will we each do next?

Yves Rees, Senior Lecturer in History, La Trobe University

Mixed Relations: Asian-Aboriginal contact in north Australia – Regina Ganter

This beautiful book (with contributions also from Julia Martinez and Gary Lee) turns the map upside-down, to examine the continent’s entanglement with Asia starting centuries before the arrival of the British.

Looking north, it begins with Macassan trepang (sea cucumber) fishermen travelling south from Sulawesi each year to trade with First Nations Australians along the coast, from Western Australia to the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Exploring the rich cosmopolitan exchange between Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, Malay and Afghan people across the country’s north, Mixed Relations is based on more than 100 interviews combined with extensive historical research.

It explores topics such as pearling in the north of Western Australia, government “protection” of Aboriginal people from Asians, and the Asian culture of Darwin.

These are stories that should be central to our national history. And especially precious to me is that Mixed Relations overflows with gorgeous images, bringing this past to life.

Jane Lydon, Wesfarmers Chair of Australian History, The University of Western Australia

Words to Sing the World Alive: Celebrating First Nations Languages, edited by Jasmin McGaughey and The Poet’s Voice

Available through SA Libraries

When Captain Arthur Phillip raised the flag of Great Britain at Warrane (Sydney Cove) on 26 January 1788, the invading nation dispossessed the original owners of more than their property. We often hear that the vast majority of the 250 Indigenous languages spoken prior to 1788 were “lost”.

As those First Nations’ elders, writers and artists now engaged in the arduous, vital process of language revitalisation are at pains to point out, language wasn’t clumsily lost, like a set of car keys down the back of the couch. Language, like land, was stolen.

Words to Sing the World Alive, is more than simply “a celebration of First Nations Languages”, as this beautiful, moving, important book humbly claims in its subtitle. It is a timely and necessary intervention into Australia’s exceptionally and stubbornly monolingual national culture.

It shows us that if history is the lock, language is the key.

Clare Wright, Professor of History and Professor of Public Engagement, La Trobe University

Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia – Billy Griffiths

Available through SA Libraries

I first read Billy Griffiths’ Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia when it came out in 2018, and loved how it charts the recognition of Australia’s ancient history. It’s a story of how settler colonial Australia slowly realised that the continent’s human history didn’t begin with colonisation, but stretched over millennia, reaching into an expanse of time that seems almost unimaginable. “The New World had become Old”, he explains.

When I returned to study last year, I read Deep Time Dreaming again and it was even better second time around. Griffiths’ book isn’t

simply about ancientness, but about the nature of Deep Time itself, patiently explained by First Nations Knowledge Holders, he acknowledges, shared by communities, measured by science and humanities, and held in archives on Country. “Beneath a thin veneer, the evidence of ancient Australia is everywhere, a pulsing presence”, Griffiths writes. This is a book I’ll keep returning to and hope others do, too, on this significant weekend.

Anna Clark, Professor of Public History, University of Technology Sydney

People Power: How Australian referendums are lost and won – George Williams and David Hume

Available through SA Libraries

Australia has changed dramatically since 1901, but the constitution still reflects the 19th century language and ideas of its authors. In People Power, George Williams and David Hume have managed to turn referendum history into a page turner. Republished following the defeat of the Voice to Parliament in last year’s referendum, it is a fascinating account of why our current system makes it so easy for popular ideas to be defeated.

The Voice in 2023, a republic in 1999, 4-year terms in 1988, these are all ideas most Australians supported, but a

lack of bipartisanship followed by similar negative campaigns, unchecked disinformation, and the age old appeal to ignorance – if you don’t know vote no – saw each of them fail.

This book reminds us that hope is not lost. Free of legal jargon, it offers practical measures that can return referendums to public ownership and make it more likely that good ideas will prevail over bad politics. Australia Day is an ideal time to consider what we want out democracy to look like.

Benjamin T. Jones, Senior Lecturer in History, CQUniversity Australia